A wide-ranging BBC survey shows almost half of Moroccans are considering emigrating and want immediate political change. So could Morocco follow in Sudan and Algeria’s footsteps and topple their leader, asks Tom de Castella.

On a balcony overlooking Casablanca’s rooftops, a man draws on his cigarette and thinks about the dream that was snatched away. Saleh al-Mansouri is only in his twenties but knows what it’s like to cross the sea to Europe. He lived in Germany for several years until his bid for asylum was rejected and he was forced to go home to Morocco.

“People go there for certain things they don’t have here,” Mr Mansouri says. Some are economic – he talks about clothes you can afford, a better lifestyle – but others are less tangible. “Like freedom,” he says, before adding: “There are many things… like respect.

“There is no care here in Morocco for the population. It’s the lack of care that makes people migrate.”

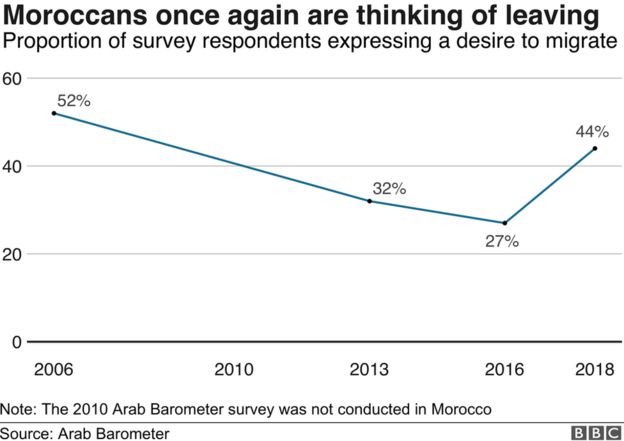

Almost half of Moroccans are considering emigrating. The proportion is up sharply after a decade of decline, a survey for BBC News Arabic indicates.

Look deeper and the survey, which covers the Middle East and North Africa in 2018 and 2019 and was carried out by research network the Arab Barometer, raises an intriguing question: is Morocco in line for mass unrest?

Mass anti-government protests in Sudan and Algeria saw sudden political change in April in what has been dubbed Arab Spring 2.0. While the toppling of Omar al-Bashir in Sudan and Abdelaziz Bouteflika in Algeria shocked most people, the clues were already there to see in BBC News Arabic’s survey.

Months before mass protest decapitated their governments, the Sudanese and Algerian survey respondents were giving answers showing they were angry, fearful and desperate.

Three-quarters of Sudanese said their country was closer to dictatorship than democracy, the highest in the region. In Algeria it was 56%, third behind Libya.

Almost two-thirds of Algerians said the country’s last elections were not free or fair, more than all the other places surveyed. Only a quarter of Sudanese and a third of Algerians believed that freedom of speech existed in their country.

One other country stood out in the data – Morocco.

Despair and frustration

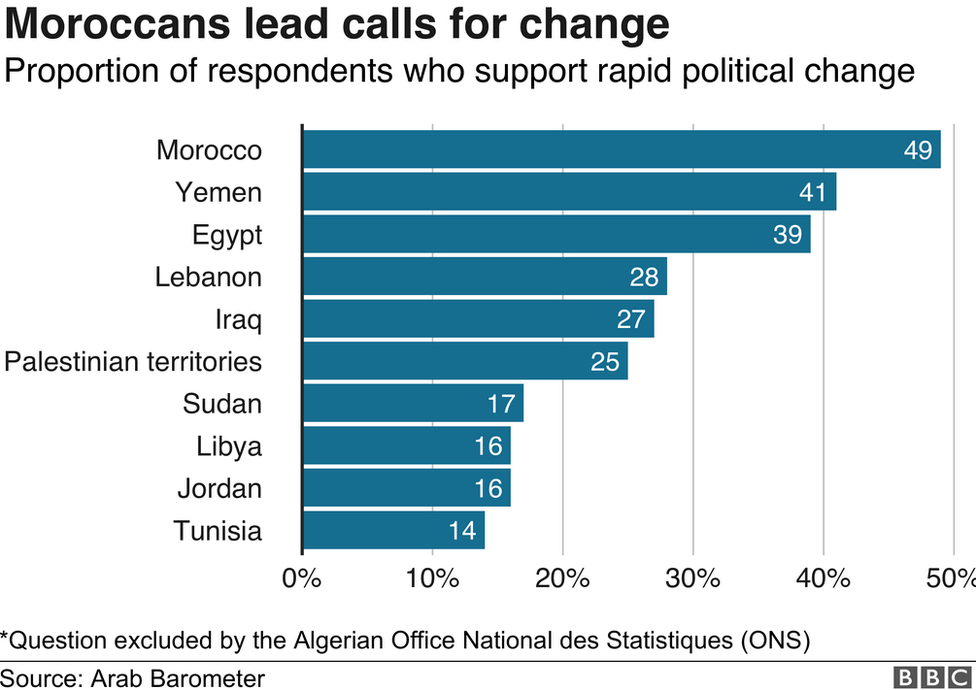

Most places surveyed indicate a desire for gradual reform. But in Morocco half of respondents wanted immediate political change.

“There is a real sense of despair and frustration amongst the youth,” says journalist and opposition activist Abdellatif Fadouach.

About 45% of the population is under 24 and on most issues the country is riven by a generational split. Some 70% of adults under 30 want to emigrate versus 22% of people in their forties. While half of over 60-year-olds have a positive view of the government, the figure for those aged 18-29 is 18%.

The Arab Spring gave younger people expectations that society would change.

Morocco is a monarchy and after protests broke out in 2011, King Mohammed VI announced a reform programme. A new constitution was introduced, expanding the powers of parliament and the prime minister but leaving the king with broad authority over the government. Many of the promised reforms were never fully implemented, Mr Fadouach says.

Turning on political elites

Patronage in the job market prevents a real market economy, he says, noting that job opportunities – such as getting taxi permits or fishing licences – are the gift of politicians in power and the Royal Palace.

“Even a glimpse of hope for tomorrow is unfortunately cut short and things go back to how they were,” he says. The appetite is there to turn on the political elite, he believes. “At any moment Morocco can witness what happened in Algeria and Sudan and before it in Syria or Egypt, Libya or Tunisia.”

Talk to the older generation and you hear a desire for continuity.

Abdallah al-Barnouni is a retired accountant living in Casablanca. He doesn’t share the younger generation’s eagerness for immediate change: “Today’s generation, today’s kids, they want to get there quickly. They want everything quickly – the car, the house, the job, they quickly want to reach a high standard of living.”

There is no sign of a violent uprising. At least not yet.

But the survey indicates that Moroccans were heavily involved in peaceful protest, behind only Yemen and the Palestinian territories, places ravaged by war or conflict. More than a quarter of respondents said they had been involved in a peaceful protest, march or sit-in. At a wider level, Morocco is a country and a culture in flux. The number of Moroccans describing themselves as not religious has quadrupled since 2013 – the fastest rate in the region.

Protests against corruption and unemployment rocked marginalised northern Morocco in 2016 and 2017 as part of a movement known as Hirak Rif. Thousands took to the streets and hundreds were detained. There were more protests in April this year when a court upheld the 20-year jail sentences given to the movement’s leaders.

The BBC contacted the Moroccan government for comment on the survey findings but did not receive a response.

The presidents toppled since the start of the Arab uprisings

- Tunisia’s President Zine al-Abidine Ben Ali left office on 14 January 2011

- Egypt’s President Hosni Mubarak was swept from power on 11 February 2011

- Libya’s President Muammar Gaddafi was killed on 20 October 2011

- Yemen’s President Ali Abdullah Saleh was ousted on 27 February 2012

- Algeria’s President Abdelaziz Bouteflika resigned on 3 April 2019

- Sudan’s President Omar al-Bashir was overthrown on 11 April 2019

In Sudan and Algeria popular discontent began in impoverished regions before spreading to the capital. Could that happen again?

“It’s very hard to predict,” says Abderrahim Smougueni, a journalist for TelQuel Arabi, a Moroccan weekly magazine. Some of the same ingredients exist in Morocco. “There’s popular discontent and frustration with the government and prime minister.” People were expecting the government to fight corruption, he says. Instead they put up taxes on the middle classes, alienating a key segment of the population.

However there are crucial differences. Sudan and Algeria are not monarchies.

Loyal army

In Morocco however the consensus view was that the king stood above politics and acted as a brake on mass protest. The question is whether that situation still holds. “Whatever people think of the government, they have faith in the king,” Mr Smougueni says. Others say it is less clear cut. “Before [the Arab Spring] there was a consensus around the monarchy,” Mr Fadouach says. “But today this belief in the monarchy might not persist.”

Once the extent of the protests against Mr Bashir became clear, Sudan’s powerful military removed the president in a coup d’état and began a violent crackdown on protestors. But in Morocco the army appears loyal to the king.

For Mr Smougueni this isn’t yet a mass movement, more a series of technical protests and strikes about reform in specific sectors of the economy such as about health and education.

And yet, a region that for years seemed impervious to change is now defined by instability. Since the Arab Spring began in December 2010 at least half a dozen countries have seen their president fall or war break out. In other words, popular protest can spread like wildfire in the Arab world. And there are no guarantees it will end well.

Red flag

Morocco has not yet had its defining Arab Spring moment – the 20 February protest movement of 2011 did not lead to fundamental change. The king is still pulling the strings and political reform has been limited.

Arab Barometer’s Michael Robbins is cautious about the idea of the monarchy being overthrown. But the data should raise a red flag for Morocco’s government, he says. “Moroccans, particularly the younger generation, are more likely to want rapid reform than citizens in other countries. They also seem closer to having a spark to ignite them.”

If not on the brink, Morocco is at a crossroads. Much now depends what the youthful majority demand of their king and his unpopular government.

Source: BBC